Sorry I had to interrupt the Kenya flow with the skiing story. We’re now back on track with more birds – I’m sure my kids will be delighted.

As a recap, in Kenya – Part 4a I introduced the Crested Lark, Southern Ground-Hornbill, Grey Crowned Crane and some Kingfishers. This selection was a bit random. so to get this second part on Kenya birds going, I made a list of the birds we saw that I thought would be interesting to write about. As in Part 4a, they first had to be not seen in the UK and I had to have something to say about them from our game drives. I found the list got longer and longer, so I’ve had to be quite selective.

The Birds of East Africa and Wikipedia have been my primary sources of information.

Little Bee-eater

This bird was so easy to miss. Why? The adjective in the name is a bit of a give-away – it’s about the same length as a house sparrow (15cm head to tail) but not as chunky, and they sit very still on a low perch watching for their prey (insects, especially bees, wasps and hornets). Cleverly, they know to remove the prey’s stinger before eating it, which they do by hitting it repeatedly on a rock or other hard surface.

Europe has one species, a larger version which I think is even prettier but which I’ve only seen once, in Brittany. My East Africa bird book boasts 20 bee-eater species including the Little and the European. We only saw this one – or rather Simon spotted it or else we would have completely missed it. It’s widespread and plentiful – I saw it in Kruger too.

Pin-tailed Whydah

And right after the bee-eater, we saw this small bird with a long tail. We had an interesting time interpreting what Simon was telling us was its name but eventually Sabine got there by looking through the book until she found it (right at the back, of course).

Only when I came to write about it did I realise it’s approach to breeding is like that of the UK’s Common Cuckoo. It lays 2-4 eggs in the nests of a number of waxbill species and lets the host parents rear its young.

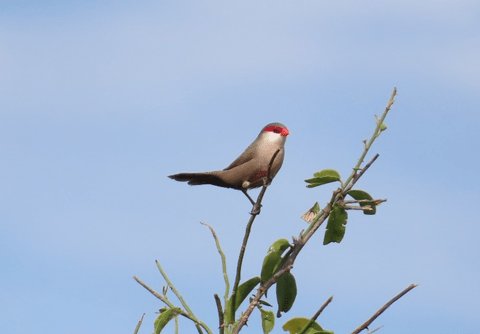

Common Waxbill

This has to be the bird world version of both wetnurse and childcare with no biological parental responsibility or involvement. Unlike the Cuckoo though, the host’s eggs are not destroyed by the foreign hatchlings and the host raises both their own and the Whydah’s young together.

Excluding the long tail, the Pin-tailed Whydah is even smaller than the Little Bee-eater. However, it too is widespread and common across a variety of habitats.

Common Ostrich

From one extreme to the other. Simon stopped the Landcruiser to observe them in the middle distance and predicted what was about to happen, even though the male was a long way away from the female. We witnessed the courtship display by the male Ostrich to the female. He headed straight for her, going past another female on the way, curved his neck back so his beak was pointing straight up to the sky, spread his wings out and strutted towards her.

She moved away from him in a hurry but then stopped. He continued his display, still advancing towards her. He had obviously impressed her because after she stopped and he reached her, he proceeded to have his wicked way with her. And when they separated, he simply walked away from her and disappeared over a ridge without so much as a backward glance. Nothing tender and loving about that relationship.

We saw quite a few Ostriches, as opposed to none in either of the Kruger visits, probably because Kruger was all scrubland; they prefer the open grassland habitat of the Masai Mara and Serengeti, which allows them some protection in using their top running speed of 70 km/h, as flight clearly is not an option. And at 2.2m in height, they are the largest bird, the fastest two legged animal on land and they lay the largest eggs of any living land animal.

They are largely herbivorous but will eat insects and other small animals. It takes 3 – 4 years for them to reach maturity and the males may take another 3 years before they mate, which is a very long time in the bird world, but then they are very large birds. Their life span in the wild can be up to 40 years.

Secretary Bird

While still on the subject of very large African birds, this is undoubtedly one of the weirdest looking birds I’ve ever seen. Adults grow to 1.3m tall and they prefer open grasslands with relatively low foliage. Their status is Endangered due to a loss of habitat.

We saw three of them – one on its own and then a pair of them on another game drive. Sadly each time we only spotted them close to the road which they then crossed in front of us and I couldn’t get a good photo, so the one above is from Wikipedia and the one below came from the San Diego Zoo website, where they have been bred in captivity.

From their beaks, you can tell they’re actually birds of prey but, even though they can fly, they find their prey mostly on foot. They feed on a wide variety of insects, reptiles, amphibians and small mammals. Extraordinary-looking birds.

Hamerkop

The Hamerkop gives the Secretary Bird a run for its money in the weird-looking department. It gets its name for the Afrikaans for “hammerhead” and it’s not hard to see why. In taxonomy, it is the only species in its Family, so it is unusual in more ways than one.

We saw them every day, often in marshland close to the road or track and they showed no signs of being disturbed by us. They are extremely versatile in their diet, preferring amphibians and fish but by no means limited to them. They find their prey by walking through water, probing in the mud and in flight. This wide dietary range makes them a very successful species and are in no way threatened.

Rattling Cisticola

We heard this bird before we saw it. It was like a rasping, rattling noise, very distinctive preceded by a series of churrs. Now I have to admit that in the book a lot of Cisticolas look alike, some very alike. We have that look-alike problem in a few UK birds – marsh and willow tits, willow warblers and chiffchaffs come to mind. A distinctive call is the best way of identifying which species it is. Simon could tell it was a Cisticola but wasn’t sure which one.

Sabine had his bird book and searched for a bird that would have that call. She found it among the 41 species of Cisticolas. It fitted the sound we’d heard perfectly. We drove on about another 200 metres, heard it again, stopped, and then saw it perched out in the open making that same rattling noise. Eureka! What an onomatopoeic moment (sorry to appear a little highbrow but I couldn’t resist – when the name for something reflects the sound it makes).

They’re a little smaller than a house sparrow and very common in grassland and scrubland habitats, feeding on insects and their larvae.

Bateleur

This bird is a medium-sized eagle and therefore large by raptor standards (70cm in length and a wingspan of 180cm, typically about 50% larger than our Common Buzzard). We saw it on two or three occasions, one very close to us and we were able to watch it losing out to a slightly larger Tawny Eagle for a tree-top perch. I also saw it a few times in Kruger – the habitats of Kruger’s scrub and open woodland and grasslands with a few trees as found in Masai Mara are what they prefer.

However, they take 6 to 7 years to reach maturity, are easily scared off their nests by predators (mainly other raptors and humans) and have suffered from habitat loss, pesticides and persecution. Despite a varied diet that includes carrion, this has meant that its numbers have declined rapidly recently such that they are on the Endangered list and although widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, it is found mainly in protected areas.

The name is unusual. It has survived in the original French form that was given to it by a French naturalist and explorer, François Levaillant (1753-1824) and means “street performer” – not sure why he chose that name. Its Latin name means “marvellous face without tail”, the lack of a tail being quite evident in the photos (the flight photo is from Wikipedia).

There are more birds I’d like to show you, so I’ll be writing a Kenya – Part 4c.