I read an interview in The Times recently. Annoyingly I can’t remember who it was (senility setting in) but he was asked who he would like to apologise to. His answer was his children – he believed that parents do so much damage to their children and he just wanted to say sorry to his for whatever harm he’d caused them. I now appreciate how right he was.

Just before Sabine and I left on this vacation, I came to realise that you can hurt your children even when you think you’re actually doing the opposite and giving them the treat of a lifetime. What you inflict on them can come back to haunt you for the rest of your life, certainly nearly fifteen years on.

I can see now that taking them on that Kruger safari in 2009 was a big ordeal for them. It also seems to have given them elephantine memories. I say that because they are able to relive their trauma in every detail as if it were only yesterday, recalling it so clearly and passionately in their warning to the next unsuspecting person with whom I’m going on safari, Sabine.

“Oh no, don’t let Dad tell the guide he’s interested in birds; if you do, that’s all you’ll see the whole time you’re out on the game drives. And he tipped the bird-mad guide more than he gave the really good one who got us a lion kill – what does that tell you?” And this cautionary tale was told by them both independently to Sabine. Without a doubt, they are scarred for life.

So when we were asked the usual opening question by the guide, this time by Simon: “What do you want to see”, I paused, thinking how best to answer without upsetting Sabine for the rest of the safari, but she stepped right in and said: “Elephants, and if there were some interesting birds, that would be great too”. Bless her, what a girl. And of course having Simon to ourselves meant we didn’t have to worry about the sensitivities and preferences of others in the jeep. We could stop and look at whatever we liked – perfect.

Masai Mara boasts nearly 500 bird species of all shapes and sizes, including 47 birds of prey. I would have been happy with 100 but we got the count up to 120 species, with quite a few more that we saw, perhaps fleetingly, going unrecorded because Simon and/or we were too busy looking at other animals to stop and investigate.

Identifying African birds is like starting bird-watching all over again. And 14 years on from the last time, I’d forgotten a lot about the birds we saw in South Africa. Most of the birds you never see in Europe, let alone in Britain, and in most cases there isn’t even an equivalent. There can often be multiple different species in a genus you’ve never heard of, most looking more or less alike.

Overall they are more colourful, more dramatic and more varied than the British birds that I and possibly you are familiar with. They’re also far harder to photograph than animals because they are generally much smaller, they don’t keep still and often they fly off just as the camera focusses.

Simon had a good working knowledge of the birds, but he wasn’t an expert, saying that he would take this opportunity to improve his knowledge. Ah, so not another bird-mad guide then – the kids would have been so relieved.

But he had a great bird book, well-thumbed, which he passed back to us when he was driving so we could look up any bird we saw that he couldn’t identify. Sabine was particularly good at that – must come with being a professional researcher. The book was Helm’s Guide to Birds of East Africa; it seemed quite complete and very informative with good pictures and details, but heavy for a field guide.

Before leaving the UK, I’d bought Collins Birds of Eastern Africa which paled by comparison. I bought it because it didn’t look like it weighed a lot – we were only allowed 15kg on the internal flights including hand luggage and I didn’t want a bird book that weighed a ton. The trouble was it was light in more ways than one. Simon’s book was so much better in every way. Between a rock and a hard place, as they say.

Bill Oddie is a keen and knowledgeable birdwatcher as well as a member of the Goodies; he has said you can never have too many bird books, a sentiment with which I heartily agree. So I bought the book that Simon had when we got back. It weighs 1.19kg, and it has been an invaluable aid to writing the Kenya stories about the birds we saw. It covers 1,448 species, about 70% of the birds found in all of Africa south of the Sahara Desert.

So where to start? I can’t cover all 120 species we saw, so I’ve made a selection of the birds that were especially memorable. Many of these are large, hence I have a photo to show you and I’ve copied photos where I don’t have one.

Crested Lark

I mention this bird first because it was the first bird we saw after climbing aboard the Landcruiser at the airstrip for the drive to the camp. They’re very similar to our skylark in size, with the crest and the colouring. They occur throughout Europe, Asia and the northern half of Africa. They’re non-migratory, so only rarely are they seen in the UK and then only as vagrants (i.e. they flew in by mistake).

We saw them a lot during our game drives, always on a vantage point like a post, a small shrub or a termite hill, and always making a racket. Like our skylark, they fly up vertically high into the sky (but unlike ours, don’t sing on the ascent), a behaviour that we sadly did not observe, perhaps because we weren’t in peak breeding season.

Southern Ground-Hornbill

This extraordinary bird constituted one of the most peculiar sightings we had and also one of the most memorable. They are very large birds, larger probably than a turkey. And with their red eye and throat wattles, curious eyelid that protrudes out over the eye, the large curved beak and short stout legs strutting about in a vast landscape, they are like no other bird that I can recall seeing.

We saw this pair looking for food about 100 metres apart on a large area of grassland. The male was the closest, so we stopped by him. When he caught a grasshopper, Simon told us he would now walk over to the female and give it to her …… which is exactly what happened. He came up to her, there was a little posturing and they performed what looked like a dance. It all seemed very chivalrous and loving.

The Safari Bookings website provides some good information about these birds:

“The southern ground hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri) has been classified as an endangered species within South Africa since 2014. The key factors contributing to this classification are loss or change of habitat, persecution, poisoning, and electrocution. Conservationists are taking steps to turn this around. Here are some interesting facts:

- Ground hornbills call together before dawn in a chorus of repeated low grunting notes that sounds not unlike a distant lion. They amplify their calls by inflating the big, red, balloon-like wattle below their bill.

- Small animals need to lie low when a party of ground hornbills is out foraging because these omnivores snap up anything – from insects and lizards to small birds, rodents, tortoises and snakes as big as puff adders.

- Ground hornbills are very slow breeders and, as a result, a pair produces just one brood of two chicks every nine years, only one of which survives. Immature birds within the social group work as ‘helpers’, caring for the single chick.

- Ground hornbills have lived up to 70 years in captivity. This makes them one of the world’s longest-lived birds, on par with albatrosses.

- Since traditional African cultures saw ground hornbills as harbingers of rain, killing them was taboo. Thus, sadly, with the passing of such beliefs, these birds have become increasingly threatened.”

The point about how slow they are to breed is astonishing – to my mind, it’s even more surprising that they aren’t extinct by now.

Grey Crowned Crane

We saw these very elegant, striking-looking birds a lot. They mate for life after a courtship dance and we always saw them in pairs. We saw them so much, at times in small flocks, say 10 or 12 birds, that it’s hard to believe that they have an Endangered status, mainly due to loss of habitat. They are the national bird of Uganda and appear on that country’s flag.

I had never seen this bird before 2023, not even in Kruger with the kids. Then I saw it three times in four months in completely different surroundings and circumstances. I took photos each time so I’ve been able to confirm that they are the same species.

The first time was in August in the garden of a hotel called La Mare aux Oiseaux near St Nazaire that backed on to marshland. It was surreal to see it strutting around the grounds, quite tame, but looking completely out of place. What we thought were the females turned out to be Common Cranes on closer examination of the photos before I wrote this part of the story. I had to check because they were different and the Grey Crowned Crane male and female are alike.

The second time was with my granddaughter later in August at Jersey Zoo. That in itself was a surprise, having only just seen it enjoying the freedom of the hotel garden. Now that I know they are endangered, its presence at the Zoo makes more sense. I only saw one there but there may well have been another in the shrubbery.

And of course the third time was on safari. Both Sabine and I recognised it from the hotel and because it was such a striking-looking bird, it seemed to us to be suited to an artificial environment like the hotel than on the plains of the Masai Mara.

They’re omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of plants and small animals and insects as they walk over the grassland. They are often closed to antelopes and other herbivores, taking advantage of the larger animals disturbing insects and other prey as they graze.

They breed all year round in the Masai Mara; we came across one sitting on its nest on the ground at the edge of a small area of marshland but I wonder what kind of protection the nest’s location offered against the area’s many predators.

Kingfishers

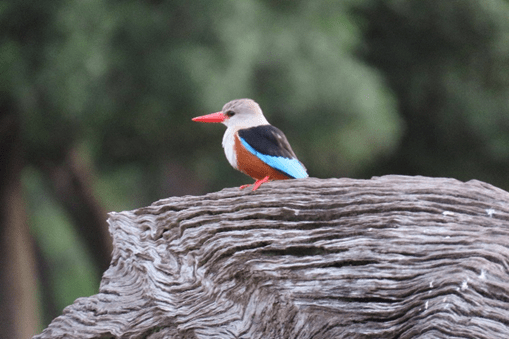

We saw 4 species of these remarkable birds: Grey-headed, Malachite, Pied and Woodland. I want to explore the first two in a little more detail, mainly because of their beautiful colouring.

The Grey-headed Kingfisher is widespread across sub-Saharan Africa, out to the Atlantic Ocean Cape Verde Islands and the Arabian Peninsular in the other direction. It’s preferred habitat is woodland and shrubbery close to water but unlike many other kingfishers, including our own and the Malachite and Pied we saw, it is not dependent on water as the medium for its food. It has many of the characteristics of the Woodland Kingfisher that we also saw, but is a lot prettier.

Simon, our guide, found this Malachite Kingfisher in the same marshland as the Grey Crowned Crane nest. Initially, only he could see it because Sabine and I were looking for a bigger bird, having just seen the much larger Pied Kingfisher, again in the same area. Simon drove round to the other side of the marsh and we saw it.

Apologies for the lack of sharpness of the bird in this photo, but first I had trouble finding it with the camera on full zoom, and then trouble getting the zoom to focus on it rather than the surrounding reeds, given its size. The photo is enlarged as much as I could before it became too grainy! Still, could be worse – it’s not a Dwarf or Pygmy Kingfisher both of which are even smaller. At 5 inches in length, it’s about the size of a Great Tit, common UK garden bird. This is the original photo on full zoom

I’m going to end Kenya 4a here so it isn’t too long. I’ll be back with more birds soon.